The Labubu Trilemma: Part 2

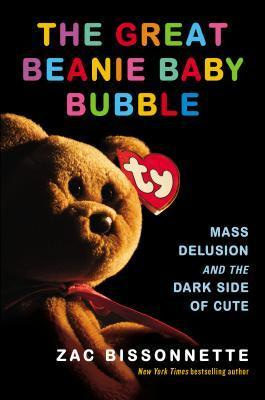

"The Great Beanie Baby Bubble: Mass Delusion and the Dark Side of Cute" Review

Author’s note: This piece is a continuation of our previous note on Labubu (link) and focuses on general research insights into one of the hottest current global consumer trends instead of a company-specific investment thesis.

The Impossible Trinity of Collectibles: Beanie Babies

In our previous note, we highlighted the challenge of maintaining the impossible trinity:

Maintaining Exclusivity & Veblen Status: Preserving Labubu's high perceived value and desirability, which is intrinsically linked to its scarcity and high secondary market prices.

Achieving Aggressive Sales Growth & Shareholder Returns: Fulfilling the corporate imperative of a publicly traded company to scale revenue and profit across its intellectual properties, particularly Labubu, to meet elevated market expectations.

Ensuring Social Harmony & Favorable Regulatory Environment: Navigating public sentiment by preventing chaotic scenes and managing the adverse effects of scalping, while maintaining positive relations and avoiding intervention from the Chinese state.

This article explores these concepts in greater detail from the perspective of Beanie Babies, one of the greatest consumer trends during the 1990s era and leverages content from the book: “The Great Beanie Baby Bubble: Mass Delusion and the Dark Side of Cute”

Beanie Babies: An Introduction to the Plush Paradox

For those who may not recall, Beanie Babies were small, under-stuffed beanbag animals, typically retailing for around $5. Conceived by Ty Warner in 1993, they were initially intended as "fun playthings for children." However, their unique "floppiness" and "poseability," achieved through PVC pellets rather than traditional stuffing, quickly set them apart from conventional plush toys. This seemingly innocuous innovation laid the groundwork for a speculative frenzy that would transform them from simple toys into coveted investment vehicles, driven by irrational exuberance and the human propensity to chase perceived quick gains.

1. Maintaining Exclusivity & Veblen Status

Warner's genius lay in his meticulous, almost obsessive, attention to product design and a shrewd, albeit often accidental, approach to supply. He personally groomed animals at trade shows, plucking around eyes for "eye contact" and blow-drying fur to enhance thickness, ensuring a perceived high quality.

The cornerstone of Beanie Baby exclusivity was the engineered scarcity. Warner frequently employed a "rolling mix" strategy, discontinuing older styles and introducing new ones, creating a "ticking clock" incentive for buyers. The concept of "retirements" was a masterstroke, initially a serendipitous outcome of supplier issues (e.g., Lovie the Lamb) that was quickly adopted to "plant the seed in consumers' minds that the Beanies they could buy on the primary market for $5 would be retired and immediately take on a higher value on the secondary market." Warner even hoarded over $100 million worth of retired Beanies in a warehouse rather than selling them, a testament to his commitment to maintaining scarcity.

Distribution was tightly controlled, exclusively favoring "mom-and-pop toy and gift shops" and famously refusing to sell to mass merchants like Walmart. This preserved a "special" and exclusive aura, preventing them from being perceived as cheap commodities. Unpredictable shipping schedules and strict order limits further fueled the "Beanie Chase," creating a palpable sense of urgency. Accidental product variations, such as the royal blue Peanut the Elephant (whose color was deemed "too dark" after a few thousand were sold), inadvertently created highly coveted "oddities" that became worth thousands.

However, the pursuit of exclusivity faced significant challenges. The soaring perceived value led to a rampant problem with counterfeits. It was estimated that "roughly one-quarter of Beanies on the market for $1,000 or more were fakes," burning high-ticket collectors and making them reluctant to pay for more rare items.

2. Achieving Aggressive Sales Growth

Beanie Babies initially struggled, with retailers hesitant to order them. However, the combination of engineered scarcity and burgeoning collector interest ignited a remarkable sales trajectory. Word-of-mouth, fueled by children bringing the pocket-sized toys to school, sparked regional interest.

The emergence of early collectors, particularly in the Chicago suburbs, who meticulously tracked variations and traded pieces, laid the groundwork for a broader market. Stories of quick profits, even if exaggerated, spread virally, creating a "feeding frenzy" and drawing in new participants. The media played a crucial role, with self-published books touting "ten-year predictions for their values" and magazines asking, "How Do You Protect an Investment That Increases by 8,400%?" Economist Robert Shiller noted that the news media, far from being detached observers, were "an integral part of these events."

The advent of eBay proved pivotal, providing an accessible online secondary market for price discovery and trading that scaled the craze nationally. By May 1997, $500,000 worth of Beanies were sold monthly on eBay. The McDonald's promotion massively amplified mainstream buzz, creating an "enormous imbalance between demand and supply" and leading to rapid sellouts and frenzied customer behavior. This culminated in Ty Inc.'s annual sales reaching an astounding $1.35 billion in 1998, with Warner's pretax income surpassing $700 million – exceeding Mattel's and Hasbro's combined earnings.

However, Warner's strategic decision to partner with McDonald's for the Teenie Beanie Babies Happy Meal promotion, while a calculated risk for mass exposure, ultimately diluted the brand's exclusivity. McDonald's offered unparalleled access to a mainstream market, producing 100 million Teenie Beanies – enough to supply every household in America within weeks. Despite Warner's intent to drive new consumers to gift shops for larger Beanies, this mass exposure, paradoxically, contributed to the perception of oversupply.

By 1998 a USA Weekend poll found that 64 percent of Americans owned at least one Beanie Baby.

3. Ensuring Social Harmony & Favorable Regulatory Environment

Initially, Beanie Babies were perceived as "fun playthings for children," fostering a "warm and fuzzy" sentiment among early collectors. However, as the market transformed into a speculative arena, this social harmony rapidly eroded.

The shift from a children's toy to an adult investment led to irrational and extreme behaviors. People went to astonishing lengths: collectors "racked up $1,000-per-month long-distance charges" calling stores nationwide , some ordered "a hundred Happy Meals and asked the cashier to keep the food" just for the Teenie Beanies , and one collector "smashed her two-year-old’s head into a door while rushing a gift shop with a mob."

Financial recklessness was rampant, with individuals using "daughter’s $100,000 college fund as capital" for Beanie Baby handbooks or spending over $100,000 on collections believing they would fund college educations. The mania even devolved into criminality and violence, including theft of Teenie Beanies from McDonald's, armed robbery of gift shops for $5,000 worth of Beanies (leaving cash untouched), and tragically, murder over a "Beanie Baby deal gone bad."

Even a U.S. Trade Representative, Charlene Barshefsky, was stopped at Customs for illegally acquiring Beanie Babies in China, leading to public denouncement.

Retailers, too, faced immense frustration due to unpredictable shipping, unfilled orders, and price gouging by resellers, leading some to stop carrying the products altogether. Ethically, the toys became too valuable to be given to children in therapy groups for dying parents, as parents prioritized perceived investment gains over the children's comfort.

The Collapse of the Trinity: An Inevitable Implosion

The Beanie Baby bubble's collapse was not a sudden event but a multi-stage process, driven by the inherent contradictions of Ty Inc.'s impossible trinity.

The market became oversaturated by 1998. In January 1999, Ty released 24 new Beanie Babies, the largest product introduction in its history, overwhelming collectors and making it "virtually impossible to collect 'all' of the Beanie Babies." "Overproduced 'commons'" began stacking up and selling below retail, sometimes "two for $6" at flea markets.

The loss of perceived value was critical. In January 1999, the expected price increases for newly retired pieces did not materialize, shattering the ingrained belief that "Beanies going up in value upon retirement was not an immutable law of nature." eBay's transparency, which once fueled the craze, now exposed the market's stagnation and decline in real-time, leading to widespread pessimism.

Warner's desperate attempt at a "surprise" mass retirement followed by an online "vote" to "bring them back" was widely perceived as an "obvious gimmick" and "transparent market manipulation," further eroding consumer trust and the brand's mystique. The media, once amplifying the craze, became "bored."

Finally, the shift in consumer interest to new fads like Pokémon, coupled with the arrival of retired Beanie Babies in discount stores like Dollar Tree, signaled the complete end of their exclusive aura and investment fantasy. The "warm and fuzzy" sentiment was replaced by the unsavory reality of "creepy, belligerent men" and women "carting wheelbarrows full of Beanie Babies" even when they couldn't afford basic necessities for their children. Ty's annual sales fell 25% in 1999 and plummeted by over 90% by the early 2000s.